- Home

- Errol Lincoln Uys

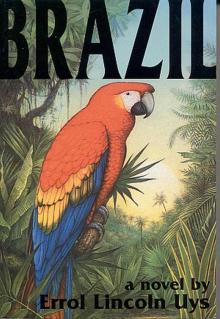

Brazil

Brazil Read online

Praise for Errol Lincoln Uys’s BRAZIL

“A masterpiece! Brazil has the look and feel of an enchanted virgin forest, a totally new and original world for the reader-explorer to discover.” — L'Express, Paris

*

“Pulsing with vigor, this is a vast novel to tell the story of a vast country. Uys recreates history almost entirely "at ground level," even more densely than Michener, through the eyes and actions of an awesome cast of characters. — Publisher’s Weekly

*

“Uys has interwoven five centuries of Brazilian history and generations of two fictional families into a massive, richly detailed novel, Michenerian in sweep and scope, informative and intriguing. Uys has a sense of pace and an eye for detail that rarely fail him. — Washington Post

*

“No one before knew how to bring to life Brazil and her history. Uys's characters are brilliant and colorful, combining elements of the best swashbuckler with those worthy of deepest reflection. Most stunning is that it took a South African, now a naturalized American, to evoke so perfectly the grand but interrupted dream that is Brazil. — Le Figaro, Paris

*

“Uys smoothly interweaves a series of self-contained episodes into a sprawling saga that spans five centuries. The richness and authenticity of the setting and the historical detail make the investment in this lavish drama eminently worthwhile.” — Booklist

*

“Uys has accomplished what no Brazilian author from José de Alencar to Jorge Amado was able to do. He is the first to write our national epic in all its decisive episodes, from the indigenous civilization and the El Dorado myth, everything converging like the segments of a rose window to that reborn and metamorphosed myth that is Brasilia. He is the first outsider to see us with total honesty and sympathy and full empathy with the decisive moments in our history and their spiritual meaning. Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay are unsurpassed in our literature and evoke the great passages of War and Peace.” — Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

*

Dynamic, excellently researched, free from the eternal stereotypes about Brazil. — Estado do São Paulo

*

Uys's unsentimentalized chronicle combines great adventure with an impressive level of research. His intermingling of real historical figures with the fictional Cavalcantis and da Silvas create an aura of verisimilitude that makes history come alive. The epic history of Brazil has been accorded its due in this panoramic novel. — Magill Book Reviews

*

The reader is entranced from the moment he is introduced to the young cannibal Aruana until the story ends with Amilcar da Silva gazing from a Brasília skyscraper at the vast sertão, the heart of the country that was unconquerable for nearly five centuries. The writing skill of Uys is evident in the way he has taken graphic stories from periods of Brazil's history and developed them into a balanced novel that equals any of the epics of James A Michener.— Nashville Banner

BRAZIL

A Novel

Errol Lincoln Uys

For my wife, Janette, with love and thanks

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE The Tupiniquin May 1491 - April 1500

BOOK ONE The Portuguese March 1526 - April 1546

BOOK TWO The Jesuit March 1550 - September 1583

BOOK THREE The Bandeirantes August 1628 - November 1692

BOOK FOUR Republicans and Sinners October 1755 - April 1792

BOOK FIVE Sons of the Empire August 1855 - March 1870

BOOK SIX The Brazilians November 1884 - December 1906

EPILOGUE The Candangos April 1956 - April 1960

Afterword March 2000 - April 2000

Glossary

Genealogical Charts

Maps

Author’s Note

About the Author

Publication History

THE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE to BRAZIL

A free online guide with a wealth of photos and illustrations giving a unique insight into the novel and its creativity.

I searched for the story of Brazil for five years, a literary pathfinder in quest of the epic of the Brazilian people. In this guide, I also share my private journal kept on a mighty trek of twenty thousand kilometers across the length and breadth of a vast country.

Discover the magic that goes into the making of a monumental novel with a first draft of three-quarters of million words written in the old-fashioned way, by hand! A quest driven by a passion for writing and storytelling.

Links to the Illustrated Guide to Brazil can be found at the end of each Book Section enhancing the reader's enjoyment of a spellbinding saga “with the look and feel of an enchanted virgin forest, a totally new and original world for the reader-explorer to discover.”

Errol Lincoln Uys

Boston, Massachusetts

PROLOGUE: The Tupiniquin

I

May 1491

The boy was sitting beside a branch of the river that marked the end of his people’s place. These lesser waters struggled through the clan’s fields, their way broken here and there by the trunks of fallen trees, until their stream was lost in this green island.

He was Aruanã, son of Pojucan, and stood taller than most boys of his age. His mother, Obapira, had counted the first four or five seasons following his birth but then stopped, for the next age that mattered would come when he was ready for manhood. Now he had reached this stage. His limbs were well formed, his shoulders sturdy and straight. His jet-black hair was shaved back in a half-moon above the temples, from ear to ear, and his eyebrows were plucked. His lower lip was bored through in the custom of his people, and in it he wore a plug of white bone as large as his thumb.

Aruanã dangled his feet in the cool water. No one ever came here, because it was too shallow for bathing and the fish were few and miserable, but such a place suited his thoughts this afternoon.

Could he not remember, two Great Rains past, when he would lie awake in the longhouse, listening to the sacred music from the clearing, rhythms that held back the sounds of the jungle, as the villagers sang the praises of his father, Pojucan, the Warrior, Pojucan, the Hunter? But Pojucan had stopped going to the celebrations and would hunt alone, often without success. And when Pojucan had become an outcast, so had his son, who was teased and taunted by his companions.

When they played the games of animals, Aruanã had to be the small rodent, Kanuatsin, who lived at the edge of the forest, and was forced to dash about, squeaking shrilly, until the others pounced upon him. At the river, they would lie in wait and ambush him when he went to swim: “Run, Aruanã, run to your sisters! Hurry to the fields of the women, for you’ll never be a warrior!”

These torments had begun only after his father started to walk alone. Aruanã’s early childhood had been happy: days of riding to the fields in the soft fiber sling at his mother’s side, and playing in the sands while she worked with her digging stick, until he was able to stalk small birds and insects with the little bow and arrow made by Pojucan. Twice within the first five Great Rains of his life, the people had abandoned the village for the forest; but, to Aruanã, the migrations had been a tremendous adventure. Nor had he felt fear when his people prepared for war: As far back as he could remember, not a single enemy had got beyond the heavy stakes that protected his home. And hadn’t he himself survived this long without being touched by the beings that dwelt in the depths of the forest and were known to devour children?

No sooner had this thought entered his mind than he detected a movement a little way downstream at the edge of the water. He sat absolutely still, his eyes riveted on the place where the undergrowth had been disturbed, listening intently for a sound.

Was it Caipora, stunted forest spirit, of whom his people spoke only

in whispers? No one he knew had actually seen the tiny one-legged naked woman who hopped around in the shadows, and this was their good fortune, for her gaze brought the greatest misfortune to whoever looked into those fiery red eyes.

To his relief, it was not Caipora but the young otter, Ariranha, who peeked out at him, made some tentative gestures toward the water, and then dashed back into his hiding place. Aruanã did nothing that might alarm the little animal. After a while, there was a slight rustling sound as the otter poked his broad muzzle through the leaves and then took to the water.

Aruanã pictured the otter splashing upstream to his family and knew that he, too, must leave this place. The sun would be on the fields beyond, but its light was fading from the roof of the forest and it would soon be as night where he stood. He would want to think of himself as bold as Ariranha, but even a warrior like his father could fear this dark.

And what more does Pojucan fear? a voice within him asked. What has he done to make his people see him worse than an enemy?

It was true. Even those they took prisoner were more welcome in the clan, for as long as permitted by the elders. The sisters of his people would take the captives into their hammocks; they would be feasted and fed; songs would be sung about them. But, for Pojucan, there was only silence. And more than this, for Aruanã had observed that other men looked at his father as if he were invisible.

Aruanã emerged from the trees at the top of a gentle rise that sloped toward the village. An ugly tangle of scorched creeper and shrub marked where his people had slashed and burned the forest. Trees that had survived the flames stood black and stark against the sky; others lay uprooted and shattered in the ash. Farther down, beyond this uncleared land, were patchworks of plantings of manioc. In the language of his people, mandi meant bread and oca the house.

The village below was the largest his people had built, and had been enclosed by a double stockade of heavy posts lashed together with vines — two great circles that protected the five dwellings arranged around a central clearing. These malocas were no rude forest huts but the grand lodges of the five great families of the clan, and in each there lived more than a hundred men, women, and children. Two bowshots in length, or sixty paces, ten paces broad and of the same height, they were raised by an elaborate framework of beams and rafters held together with twigs and creepers and thatched with the fine fronds of the pindoba palm.

Aruanã passed through the stockade and was heading toward his maloca when a boy came up to him and announced: “Naurú has asked for the feathers of Macaw. We have been called to listen this night.”

Aruanã was delighted: This meant that he would soon be taking his first step toward manhood.

Naurú, the pagé — prophet, seer, medicine man — had been keeping his eye on this group of boys for some time. Now he had given the word that the brilliant red and blue macaw feathers of his rattles needed replacing, his way of indicating that the boys must prepare for initiation.

Tabajara, the elder of Aruanã’s maloca, summoned his wives, and for two hours submitted himself to their attentions. There was Potira, little more than a child, with small, firm breasts and wide eyes; Sumá, who swam like a fish and had a magnificent body that brought great pleasure when he was alone with her; and Moema, “Old Mother,” who had come first and never let the others forget this.

When Tabajara’s body had to be painted, Old Mother would not let anyone else collect the colors from the fruit of the genipapo and the berry of the urucu tree — the one blue-black, the other an orangy red. Her fingers traced the most striking patterns on Tabajara’s flesh. Sharp black strokes accented the permanently tattooed marks on his chest — as many stripes as the enemy he had slain. She filled in between the slashes with the red of the urucu. From his midriff down, she divided the marked part of his body into sections, painting half red, the other black, and repeated these designs on his back.

Of course, she could make life difficult, with her sharp tongue and interfering ways; still, he’d secretly allow that there was more in Old Mother than in the others.

He saw Aruanã enter the maloca and caught Old Mother’s look as she followed the boy’s progress toward the far end of the house.

“I see his unhappiness,” Old Mother said. “It is not good that a boy must live with this.”

“A boy must learn many things,” Tabajara replied, “beginning with what he hears this night.”

“This is the trouble of——”

“One who must not be named,” he said quickly. “It was not on my lips,” she snapped at him.

“But in your thoughts?”

Her reply was to work the urucu dye onto his back with angry jabs.

Tabajara didn’t want to discuss this problem with Old Mother. The boy’s father had disgraced the clan, a dishonor that rested heaviest upon his maloca, since all under its roof were of the same blood. He saw Aruanã go to his hammock, and made a mental note to watch the boy closely for any sign of the weakness his father had shown.

Potira was on her knees, with Sumá, working on one of the few items Tabajara valued as a personal possession: a majestic cloak of brilliant scarlet made of hundreds of ibis feathers, selected with the greatest care for uniformity of size and color, linked together one by one with fiber string and attached to a cotton backing.

Tabajara also prized his other feather adornments: a high headdress of bright yellow and an ostrich bustle he’d wear on his rump.

Now only his face remained to be painted, but before Old Mother attended to this, she inspected him closely — and gave a little cry of triumph when she found a tiny hair at the edge of an eyelid. He gritted his teeth, great warrior that he was, when Old Mother plucked out the offending growth, gripping it with the edges of two small shells.

His face finally painted, Tabajara put the finishing touches to his appearance: He slipped a green stone, twice the size of the simple bone plug worn by Aruanã, into the hole in his lower lip, making it protrude in a way that brought murmurs of approval from his wives.

It was the first time the boys had seen the elders in full dress for their benefit alone. They sat in a semicircle on the ground between the malocas.

Tabajara was shorter than most men of the clan, but with his tall diadem he appeared as a giant before the boys.

“Sleep soundly this night, O Macaw, bird of the forest, wing of our ancestors,” he said. “Sleep soundly, for those that will seek you are as worms of the dawn. How our enemies will rejoice when these poor things are sent against their villages.”

His words were greeted with approving noises from the other elders, and the men, who stood around the clearing, echoed their feeling between gulps of fresh beer from the gourds passed among them.

Aruanã wanted the earth to take him when Tabajara, who had been pacing in front of them, stopped opposite him, the light from the log fires deepening the shades on his body and making his appearance as fearsome as anything Aruanã imagined among the spirits that filled the darkness.

“To your feet, boy!”

Aruanã scrambled up.

“Step closer to the fire so all may behold.” When the boy was in the light, Tabajara went on: “Tell me, my child, why there is hope that you will find the feathers of Macaw.”

Aruanã felt his heart pounding in his chest. “It is my wish to be a man of this tribe,” he said, with firmness that surprised even him. “This is my first duty, to get the pagé’s feathers, and I will not fail.”

“Strong words, my child, but to find Macaw, you have to enter the forest alone. There will be no warriors to silence your whimpers. What if Caipora dances in your path? What if the one who seeks tabak is there?”

Tobacco Man, a specter like the woman who hopped on one leg, lay in wait for lone warriors and demanded the sacred herb, attacking them if they failed to supply it. “I cannot say what I will do.”

The boy was honest, Tabajara thought. He was surprised that this son of the nameless one should answer so forthrightly an

d show so little fear in front of the elders. Many boys would be too frightened to utter a word.

Suddenly, all eyes turned as out of the shadows crept an ugly figure, mumbling incoherently. Among his people, Naurú was the only one with a physical defect — a bent back and twisted leg. Ordinarily among the Tupiniquin, deformed children were killed at birth, for their tortured bodies revealed the displeasure of the spirits. But Naurú’s mother had disobeyed this dictate and hidden him in a secret place at the edge of the forest, until the passing of several Great Rains, and his survival was seen as miraculously intended by those same spirits who would have condemned him. The terrifyingly lonely time in a shelter his mother had scratched out of a riverbank had left him with a cold, solitary manner and a certain ignorance of those things boys of his age feared about the forest. He soon came to the attention of the former village pagé, who had led him to the secrets of that mystical world where ordinary men were interlopers.

When Naurú approached him, Aruanã’s earlier bravado vanished under the icy stare of the keeper of the sacred rattles.

“I know this boy,” Naurú said, not mumbling now but in a voice that all might hear. “He is from your maloca.”

“There are three children in my house who seek your feathers,” Tabajara replied. “Aruanã is one.” Tabajara approached any confrontation with Naurú with extreme caution.

The village had no chief as such, the elders sharing in its leadership, but Tabajara’s presence was generally acknowledged as the most imposing, especially when Tabajara led the warriors of the clan. Only one other man held a position of equal respect - Naurú.

“Why, when he stood up, did I feel something dark arise between us?”

“I cannot answer this,” Tabajara said. He quickly saw that it had been a serious mistake to put the boy where he would attract attention.

“This is the child of a man who has brought dishonor to his people,” Naurú continued.

Brazil

Brazil